What Is a Capital Stack?

Never miss an Invest Clearly Insights article

Subscribe to our newsletter today

Every real estate deal needs funding, which is why real estate syndication and private equity investments have become so widespread. However, where that money comes from and in what order it gets repaid isn't random. It's structured carefully, layer by layer, in what's known as the capital stack.

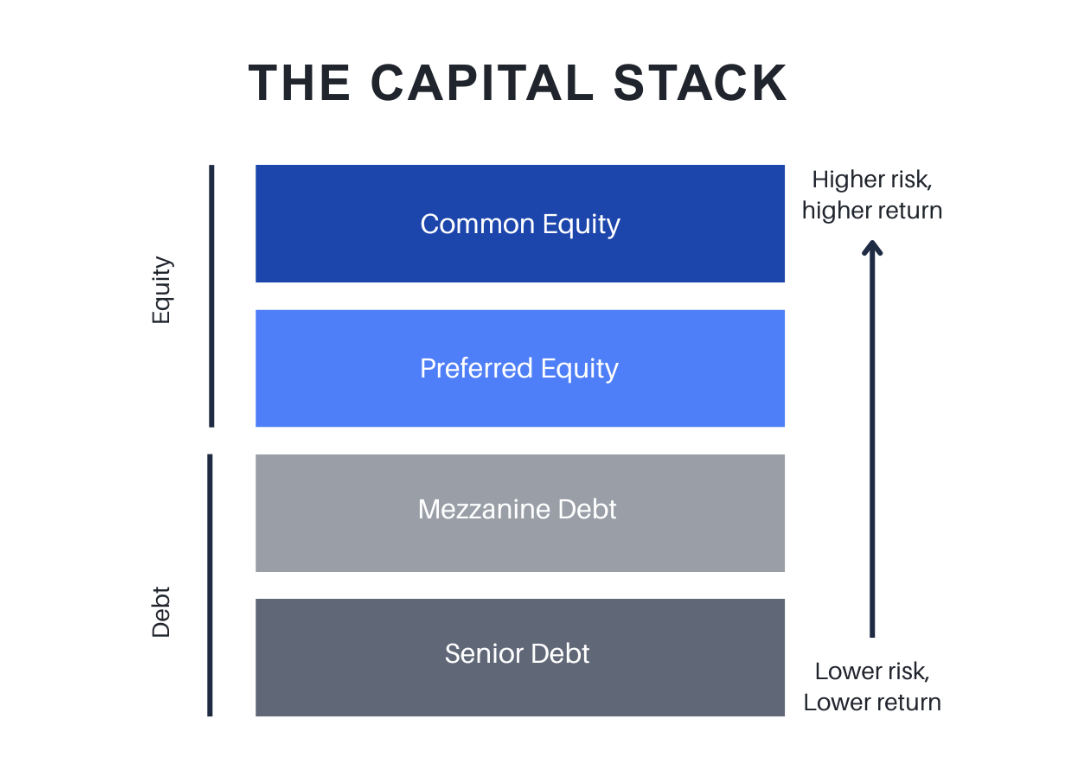

At its most basic, the capital stack definition refers to the structure of all the capital used to finance a real estate project. It outlines who contributed money, how much they contributed, and in what order they will be repaid. So, what is a capital stack, really? It's a hierarchy, often visualized as a stack, that includes different layers of funding, like senior debt, mezzanine debt, preferred equity, and common equity. Each layer comes with its own level of risk, return, and control over the asset.

Capital Stack Definition in Commercial Real Estate Transactions

In real estate finance, the capital stack refers to the complete structure of capital that funds a project. It's a layered framework that ranks each source of capital by its priority in receiving returns and absorbing risk. This stack includes a mix of debt and equity, with each layer carrying different rights, responsibilities, and expectations for return.

At the top level, the capital stack answers two questions: Who gets paid first? And who takes on the most risk?

The layers of the stack are typically organized in the following order:

- Senior Debt

- Mezzanine Debt

- Preferred Equity

- Common Equity

Those at the bottom of the stack (such as senior lenders in first lien position) have the highest priority in repayment and are exposed to the least risk. In contrast, those at the top—typically common equity investors—are the last to be repaid, but they have the highest potential upside if the project performs well.

This hierarchy affects returns as well as control. Lenders and preferred equity holders often have legal protections or negotiated rights that can influence decision-making, especially during times of financial distress.

Debt in the Real Estate Capital Stack

In real estate investing, debt refers to borrowed capital that a developer or operator uses to help finance a property's acquisition, development, or improvement. It's typically the foundation of the capital stack, covering a large portion (up to 70%) of the total project cost (total capitalization expenses). These costs include the purchase price of the property, plus all the additional expenses required to make the project operational, such as renovation budgets, legal fees, financing costs, and closing expenses.

Once the loan is in place, the borrower (typically the real estate operator or sponsor) makes regular payments to the lender. These payments include both:

- Principal: the original amount borrowed

- Interest: the cost of borrowing the money, usually expressed as a percentage rate.

Because debt holders are at the bottom of the capital stack (meaning they have first priority when income is distributed), they carry the least risk. However, they also receive a fixed return and do not share in any profits beyond what's contractually agreed upon—unlike equity investors, who may earn a portion of the upside.

Equity in the Real Estate Capital Stack

Equity represents ownership in the property. The project sponsor and external investors (Limited Partners/LPs) contribute equity capital to cover the portion of the project's total capitalization that is not financed through debt. Unlike lenders, equity investors do not receive fixed interest payments—instead, their returns are tied to the performance of the investment.

Equity typically sits at the top of the capital stack, meaning it has the lowest repayment priority and carries the highest level of risk. If a property underperforms or goes into default, equity holders are the last to be repaid, only after all debt obligations have been satisfied. However, this risk comes with greater potential reward. Equity investors can earn a proportional share of the project's profits, including cash flow from operations, proceeds from a refinance, and gains from the sale of the property.

The Four Primary Layers of the Capital Stack

Understanding the capital stack means knowing the different layers, how they impact repayment, and the risk to investors. These distinctions are critical for evaluating investment opportunities and structuring deals. Below are the four primary layers of the capital stack, ranked from lowest to highest risk.

Senior Debt

Senior debt is the foundational layer of financing in the real estate capital stack and represents the lowest-risk form of capital used to fund a property acquisition or development. It is called "senior" because it holds first priority in repayment, meaning that in the event of cash flow distribution, sale, or liquidation, senior debt must be repaid in full before any other capital providers receive returns.

Senior debt is typically secured by the underlying real estate asset, usually in the form of a mortgage or deed of trust. This security gives the lender a legal claim to the property, including the right to foreclose and recover the loan proceeds if the borrower defaults.

Because of its secured status and repayment priority, senior debt offers the lowest level of risk to the lender. In exchange for this security, the cost of senior debt (i.e., the interest rate) returns are lower than other financing options. Lenders seek an appropriate return for their desired duration and risk appetite. These loans generally have fixed interest payments over the loan term without participation in the property's upside or profits. An example of senior debt is a bank loan covering 65% of a property's purchase price, with a 6% interest rate and monthly payments. While regular payments are made on the loan, and the principal must be fully repaid, the lender will not benefit from any of the property's value growth.

Senior debt is considered a stable, income-generating instrument ideal for conservative lenders such as banks, insurance companies, and pension funds. However, few private investors or entities are lenders in these loans.

Mezzanine Debt

Mezzanine debt is a type of subordinate financing that sits between senior debt and equity in the real estate capital stack. It fills the gap between what a senior lender is willing to provide and the total capital needed for the project. You may know mezzanine debt as:

- Recapitalizations – Debt is used to pull out equity from a stabilized asset without selling.

- Vendor Take-Back Financing (VTBs) – When a seller provides financing subordinated to senior debt, sometimes structured like mezzanine capital.

- Sponsor/GP Financing – In some cases, mezzanine capital is used specifically to fund the sponsor's equity share in a deal (a.k.a. "GP co-invest loans").

Unlike senior debt, mezzanine debt is not secured by a lien on the property. Instead, it is secured by a pledge of the borrower's ownership interest (also known as recourse debt) in the legal entity that owns the property. If the borrower defaults, the mezzanine lender does not have the right to foreclose on the property directly but may take control of the ownership entity through a legal process known as a UCC foreclosure.

Because it is less secure and lower in repayment priority, mezzanine debt typically has a higher interest rate, often 9-14%. In some cases, mezzanine lenders may also receive a small share of profits or future equity, known as an equity kicker, providing a potential upside if the property performs well.

For example, if a $10 million real estate project secures a $6.5 million senior loan, the sponsor might use a $2 million mezzanine loan to increase leverage without giving up equity ownership. The remaining $1.5 million would be funded with common equity.

Mezzanine debt is most commonly used in commercial real estate deals, particularly for development projects, refinances, or acquisitions that require higher leverage.

Preferred Equity

Preferred equity combines the characteristics of both debt and equity. Preferred equity shareholders have an ownership interest in the property's holding entity but with limited rights compared to common equity. Unlike lenders, preferred equity investors do not have foreclosure rights and are not secured by the property or the ownership entity. However, they may have enhanced protections in the operating agreement, such as approval rights over major decisions or the ability to take control of the property under specific conditions.

Preferred equity deals often offer a fixed return, such as an 8-12% annual preferred return, which must be paid before sponsors or common equity investors receive any profits. In some cases, preferred equity may also include profit participation once the preferred return has been paid. However, profit sharing may be limited, and investors are not exposed to the full upside.

This structure allows sponsors to raise additional capital while holding more upside gain. Additionally, they can offer investors a position that is less risky than common equity but with greater potential return than debt.

Preferred equity is commonly used in development projects, recapitalizations, or acquisitions where sponsors want to limit equity dilution but still require additional capital beyond senior and mezzanine financing. Recently, preferred equity has been used to stabilize distressed deals, which limited partners should carefully evaluate.

Common Equity

Common equity is the top layer of the real estate capital stack and represents true project ownership. It is the most subordinate position in the stack, meaning common equity investors are last in line to receive distributions and profits. Still, they also have the highest potential for return if the property performs well.

Because common equity holds a residual claim, investors are only paid after all debt obligations and preferred equity returns have been satisfied. This makes common equity the riskiest form of capital, as there is no guaranteed return. Furthermore, if the property decreases in value, that value comes off the top of the equity stock. Therefore, common equity partners are the first to lose their capital when a property decreases in value. However, in exchange for this risk, common equity investors can benefit from ongoing cash flow, property appreciation, and profits upon sale or refinance.

Common equity holders also participate in decision-making through ownership rights. However, in most syndications or real estate funds, control is concentrated in the hands of the general partner or managing member. In these structures, passive investors contribute capital as limited partners and receive a share of profits in proportion to their investment.

Because of its unlimited upside, common equity is essential for aligning the interests of sponsors and investors. It is typically the first capital invested by the sponsor and the last to be repaid, reinforcing the sponsor's commitment to the project's success.

How to Evaluate a Capital Stack in Real Estate Investing

Evaluating a capital stack is critical when analyzing any real estate investment as an LP. A well-structured capital stack aligns the interests of investors and lenders, supports the project's financial stability, and maximizes the probability of success. A poorly structured capital stack, on the other hand, can expose the investment to unnecessary financial strain, excessive leverage, or misaligned incentives.

Composition and Proportions of Each Layer

The capital stack is made up of a combination of senior debt, mezzanine debt (sometimes), preferred equity, and common equity. Common capital stack composition ranges include:

- Senior Debt: Often accounts for 50–70% of the total project cost.

- Mezzanine Debt: May make up 10–20%, if used.

- Preferred Equity: Commonly contributes another 10–20%.

- Common Equity: Typically ranges from 10–30%, depending on how much debt the sponsor is willing (or able) to use.

Higher proportions of debt can increase returns to equity holders when the project performs well but also increase the risk of default if income is disrupted.

Assess Debt Terms and Risk Buffers

Look beyond just the interest rate. Focus on the terms of the senior loan and any mezzanine financing. Are there balloon payments, prepayment penalties, or aggressive assumptions about refinancing? Does the project have a healthy debt service coverage ratio (DSCR)? Ideally, you want it to be 1.25x or higher to provide a cushion during lean months.

The more breathing room the project has to cover debt payments, the more protected you are as an LP.

Understand Preferred Equity and Promote Structures

If the capital stack includes preferred equity, find out whether it is institutional or from insiders. Preferred equity is typically paid before common equity and often has priority over LPs in distributions. Additionally, review the promote structure. The promote, or sponsor's carried interest, refers to the share of profits the sponsor earns after certain return benchmarks are met. While it incentivizes strong performance, an overly aggressive promote structure can delay returns to LPs and misaligns incentives.

A high promote or aggressive preferred return hurdle could delay or reduce your returns as an LP.

Match the Stack to the Strategy

Different strategies require different capital structures. A stabilized cash-flowing asset might support more debt, while a development project or value-add deal might use more equity to reduce risk. The capital stack should align with the nature of the deal, not be structured just to boost projected returns.

Why Sponsors Borrow Instead of Only Raising Equity Capital

When commercial real estate sponsors structure a deal, they rarely (if ever) rely on 100% equity to fund the investment. Instead, they typically combine equity capital (raised from LPs) with borrowed funds. Here are four key reasons sponsors choose to use debt instead of raising only equity:

- Equity Is Limited and Dilutive

Raising more equity requires giving up more ownership and sharing future profits with additional common equity holders. Debt, by contrast, offers capital without giving up long-term upside. It allows sponsors to retain greater control and preserve equity stakes while funding larger deals. - Diversification and Scale

Borrowing enables sponsors to spread their equity across multiple assets, reducing exposure to any single property or market. This leads to better risk-adjusted returns and operational scale. For example, instead of buying one $10M property outright, a sponsor can buy four by financing 75% of each. - Interest Is Tax-Deductible

Debt financing creates a tax advantage by allowing sponsors to deduct interest payments from taxable income. This lowers the effective cost of borrowing and increases post-tax cash flow—an advantage equity capital doesn't offer. - Enhancing Returns Through Positive Leverage

When a property's income exceeds the cost of debt, the excess cash flow increases returns to equity investors. This is known as positive leverage and is one of the most common tools sponsors use to boost return on equity (ROE), assuming conservative underwriting and stable performance.

Questions to Ask When Evaluating a Capital Stack

A well-constructed capital stack should align with the investment strategy, support the project's financial health, and provide transparency around how capital flows through the deal. Use the questions below to evaluate whether the structure makes sense, the incentives are aligned, and your capital is adequately protected.

- Is the capital stack clearly outlined (senior debt, mezzanine, preferred equity, common equity)?

- Are the percentage contributions of each layer reasonable for the deal type?

- Does the leverage level (LTV) align with the asset's risk profile?

- Do I understand my position in the capital stack (e.g., common equity)?

- Are there any capital sources ahead of me in the waterfall (e.g., preferred equity)?

- Is there enough cash flow coverage to safely repay debt before equity?

- What is the interest rate on senior and mezzanine debt?

- Are there any balloon payments, refinance risk, or unfavorable covenants?

- Is the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) 1.25x or higher?

- If there is preferred equity, is it institutional or insider capital?

- Is the preferred return reasonable (e.g., 8–10%) and well-structured?

- Does the promote structure favor alignment, or overly enrich the sponsor?

- Does the capital stack fit the business plan (e.g., value-add, development, core-plus)?

- Is the structure designed for long-term success or just to boost projected IRR?

Evaluating Deals Means Evaluating Debt and Equity Structure

Whether you're evaluating a stabilized acquisition or a ground-up development, understanding the capital stack clarifies where your capital sits, what protections you have, and how your returns are prioritized. Smart investors don't just underwrite the property; they underwrite the structure behind it. If the capital stack doesn't make sense, the deal doesn't either. The more deals you evaluate, the faster you'll be able to identify capital stacks that don't align with the asset's business plan.

Written by

Invest Clearly empowers you to make informed decisions by hosting unbiased reviews of passive investment sponsors from verified experienced investors.

Other Articles

Investor Experience Index: 2025 Wrap Up

We’ve analyzed review data from 2025 to uncover surprising trends in private real estate.

The New Approach to Sponsor Due Diligence in Private Real Estate

Start your due diligence with the sponsor and the business plan before focusing on the real estate asset.

Is Private Equity Coming to Your 401(k)?

A new executive order could lead to private markets getting access to 401(k) capital. Learn how a new wave of capital and liquidity demands could affect private real estate.

What 2025 Fundraising Data Reveals About LP Capital Allocation in Private Real Estate

Private real estate fundraising saw a rebound in 2025, marking the first year-over-year increase in annual capital raised since 2021. According the PERE Fundraising Report Full Year 2025, total fundraising reached $222 billion, up 29 percent from the $172.4 billion raised in 2024.

Limited Partners in Private Real Estate and Private Investments

If you’re exploring private real estate investing, you’ve likely encountered the term “limited partner” or “LP.” Understanding this role is essential before committing capital to any private market fund

How Moving Up the Capital Stack Can Reduce Your Investment Risk

At the height of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, Buffett invested $5 billion in Goldman Sachs as preferred equity. Here's why....